From Peking University to UCLA, then to MIT, and finally back to Peking University, Associate Professor Wenliang Huang of the College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering at Peking University has traveled across the globe in his pursuit of knowledge. His scientific aspirations are woven into the periodic table of chemical elements, spanning from Element 21 to Element 58, Element 90... and even Element 103.

01 "Chemistry is My Career"

During his ninth grade, Wenliang Huang was introduced to academic competitions and naturally gravitated toward chemistry—his academic forte—as his primary focus. “If you pursue science or humanities, Peking University is where true scholars belong.” These words from a teacher at Shanghai High School planted a deep-rooted aspiration in his heart as he immersed himself in competition preparation.

Driven by the combination of natural interest and unwavering effort, Huang won a gold medal in the National High School Chemistry Olympiad and was selected for the national training team, securing a guaranteed admission offer to any university in China. Fueled by his admiration for the scientific world, he said, “At that time, I chose Peking University without hesitation.”

During an interview for Peking University admission, a professor asked about his intended major. With youthful ambition, Huang confidently declared, "Chemistry is my career." His fearless and unwavering response drew appreciative laughter from the audience.

▲Wenliang Huang in front of his glove-box in the Laboratory at UCLA

Beyond completing required courses, Huang began research training in a computational chemistry lab in his sophomore year, yet the stubborn divergence between his theoretical predictions and experimental outcomes became a slow, grinding torment. “Interest alone might not be enough to sustain a research career—perhaps I should switch fields.” he once pondered. Still, fueled by an enduring curiosity for science, he decided to embrace research once more, aiming to pursue a PhD before making further decisions.

After taking UCLA’s entrance exams, Huang found himself waiting outside Professor Paula Diaconescu’s office, who supervised inorganic chemistry newcomers. As he glanced at the wall, a recently published paper on organometallic chemistry caught his eye. Fascinated by the unique chemical structures, he turned around and confidently expressed his desire to join her research group.

▲In 2019, Wenliang Huang (first from the left) participated in a Quantum Center event at UCLA. Second from the right is his PhD advisor, Professor Diaconescu, and third from the left is Professor Evans from the University of California, Irvine.

Like all beginners, his journey was filled with tireless effort. Countless hours operating glove boxes, late-night NMR experiments to save costs, and even sleeping on the professor’s office couch—these experiences were imprinted deeply in his memory.

“Every step forward requires immense effort.” he recalled. His PhD advisor’s parting words still resonate with him: “You are born for academia.”

▲Wenliang Huang (first from the right) at a team dinner during his postdoctoral research.

After earning his PhD, with the goal of broadening his research scope, Wenliang Huang joined the research group of renowned organic chemist Stephen Buchwald at MIT for his postdoctoral studies, focusing on organic synthesis. Transitioning to a different research group not only meant a shift in research direction but also an entirely different approach to scientific inquiry. “During my PhD, I worked independently, but in my postdoc, I found myself in a completely new environment featuring team work. This gave me valuable experience and learning opportunities.”

▲Wenliang Huang with his postdoctoral advisor, Professor Buchwald.

02 Returning to Peking University: A New Generation of Rare Earth Chemists

In 2016, Wenliang Huang was considering his future research direction. If he continued his academic career in America, he would have to explore a different field from his PhD and postdoctoral work, as new Principal Investigators typically need distinct research directions. However, this meant he could no longer focus on his beloved rare earth chemistry. Moreover, securing research funding in the U.S. posed significant challenges.

At an academic conference in Boston, Professor Yan Li, then deputy director of the Inorganic Chemistry Division at College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering at Peking University, held a brief recruitment meeting at MIT. The Inorganic Division was looking for researchers specializing in fundamental rare earth chemistry. When she saw Huang’s resume, her eyes lit up: “Wow! You’re exactly the person we’re looking for!”

▲Wenliang Huang conducted an experiment in front of the fume hood.

During his interview in China, Huang had the opportunity to speak with renowned academicians Chunhua Yan, Song Gao, and Chunhui Huang. They assured him that, at Peking University, he could continue his rare earth chemistry research without constraints.

“If I wanted to do rare earth chemistry, this would be the best place.” he realized. The necessary instruments for testing magnetic properties were just next door, and collaboration was as easy as taking the stairs to a colleague’s office. Returning to Peking University—a path he had not considered originally—turned out to be smooth and promising. “After the interview, I was certain: if Peking University offered me a position, I would definitely come back.”

After joining Peking University, Huang read the biographies and interviews of Guangxian Xu, known as the “Father of China’s Rare Earth Chemistry.”

“His excellence in rare earth separation stemmed from his strong background in quantum chemistry. Reading the works of Guangxian Xu and Lemin Li, I realized that many of my current research ideas had already been envisioned by these pioneering scientists. They were just limited by experimental and computational conditions at the time.”

As a new-generation rare earth chemist at Peking University, Huang believes that, with today’s advanced research conditions, researchers have more sophisticated tools to verify and refine the hypotheses of their predecessors—a truly meaningful endeavor.

▲Wenliang Huang posing with the periodic table.

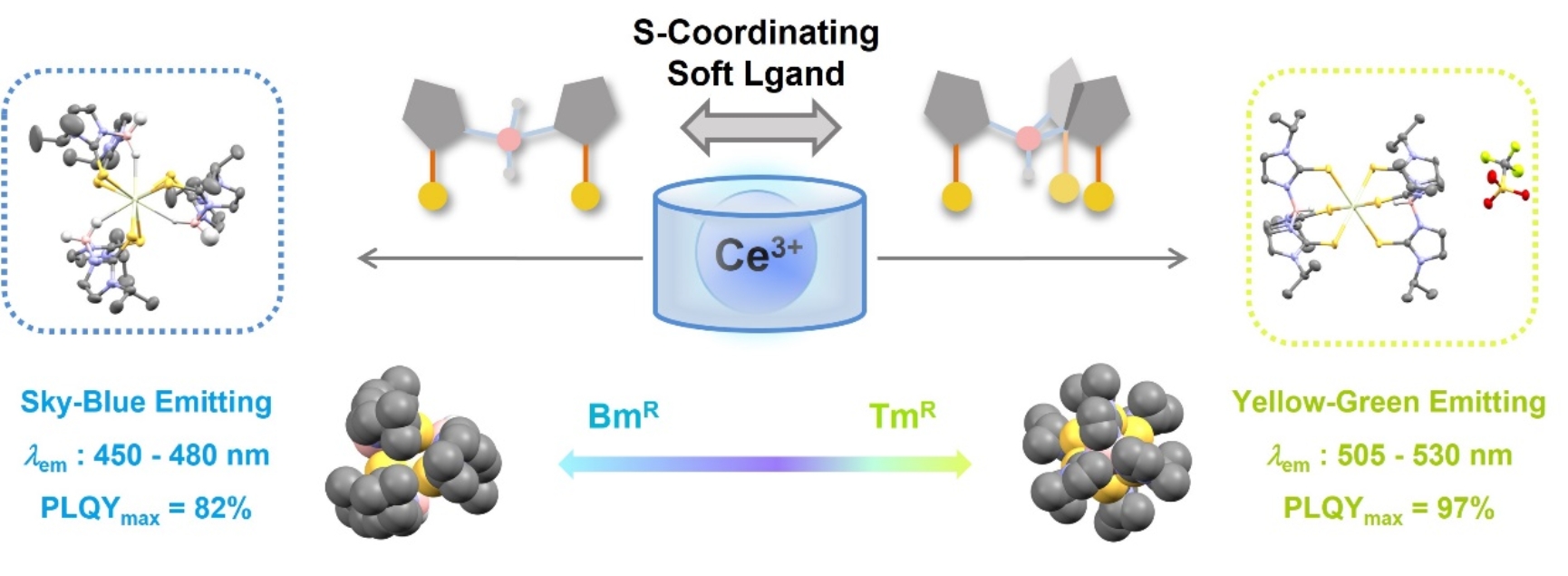

In the field of organometallic chemistry, ligands play a crucial role in modulating the properties of the metals. Designing and synthesizing specific ligand frameworks is an important approach to studying the intrinsic properties of elements. A ligand can serve as a research group's “signature.” In Huang’s group, they have developed a star ligand with a tripod-like structure. International colleagues even referred to it on social media as “Huang’s Ligand,” which delighted him for quite some time.

03 Guiding Young Minds to Find Their Own Sails

“Everyone has their own source of excitement. I find beauty in single-crystal structures, but some friends don’t understand the appeal. Helping students discover and expand their own interests is crucial.”

Since his research group focuses on f-block elements, they named themselves “CCfE” (Coordination Chemistry of f-Elements) to echo the abbreviation of the College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, CCME. Their diverse, dynamic team fosters a relaxed yet stimulating research environment, surrounding with a row of glove boxes, soothing background music, and warm lighting.

▲Wenliang Huang and students in the laboratory.

Having walked the path from student to professor himself, Huang deeply understands that passion is the best guide in research. When students facing difficult academic decisions, he always listens to them, provides his advice but respects their choices. After all, he was in their shoes not long ago and knows their concerns firsthand.

▲Wenliang Huang's research Group photo in 2024

Doctoral students form the core of his research group, while undergraduates represent the future academic candidates. Every Thursday night, group meetings are held for literature presentations and research progress reports. Students present in English to improve their speaking skills, preparing them for international collaborations. Additionally, he holds one-on-one meetings with students every two weeks, providing a private and in-depth atmosphere for discussing research challenges—or even personal issues.

▲Wenliang Huang in his office

Except guiding graduate research projects, Huang also devotes a lot of time and energy to teaching. In 2021, he opened a new course: “f-Block Element Chemistry.” This course has attracted many students, both graduate and undergraduate students, and many of them may not specialize in f-block elements but find valuable connections to their own research, gaining new inspiration.

“If you were certain that you left your key in a specific room, you would definitely find it. However, if you were unsure where you lost it, you might never recover it.” Huang loves using this everyday analogy to encourage students to pursue research boldly. “You have to try—only through experimentation will you know what works.”

As both a mentor and a companion, Wenliang Huang explores new scientific frontiers alongside young researchers while also building deep connections with them. He carefully aligns students’ backgrounds and interests with the research group’s direction, crafting unique academic growth paths for everyone. Ultimately, his goal is to empower these young navigators to sail forward independently on the vast ocean of academia and life.